Gripp — The flying letters

“Do you have a handkerchief?”

Influenza, you little demon

Wash your hands!

How to be patriotic

Masquerade

Docs with guns!

Fast, Safe, Painless!

Magic Therapy

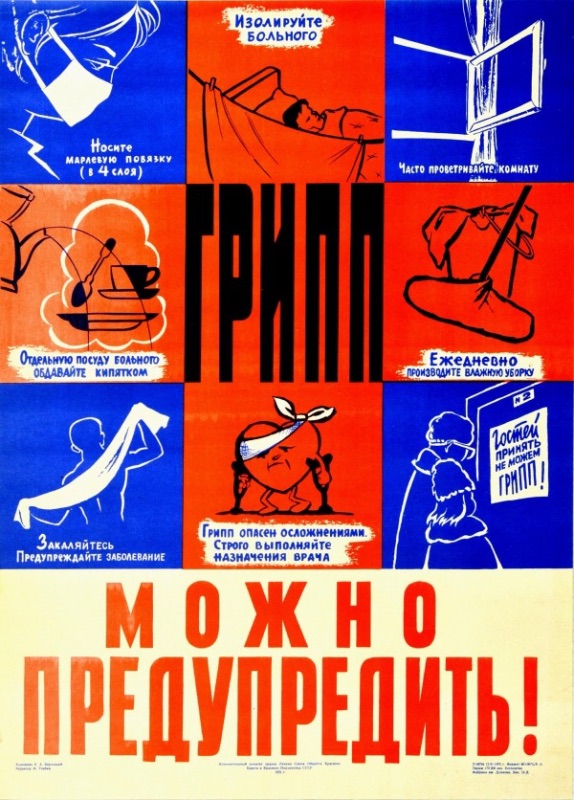

Gripp — The flying letters

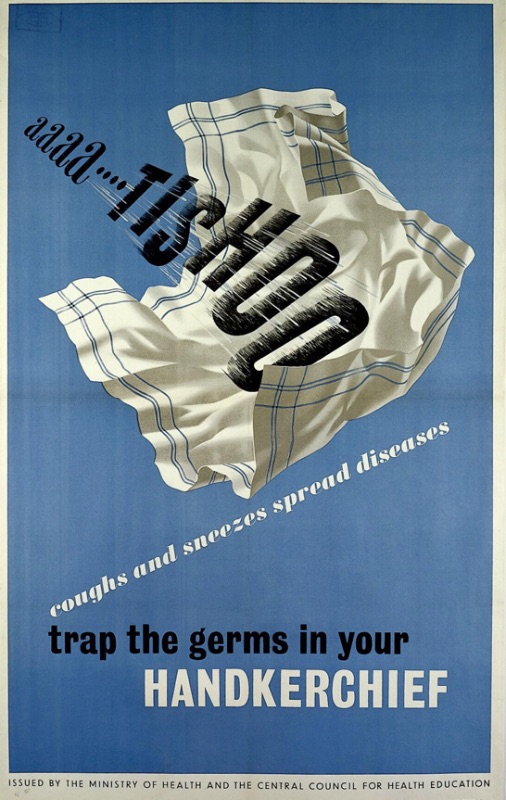

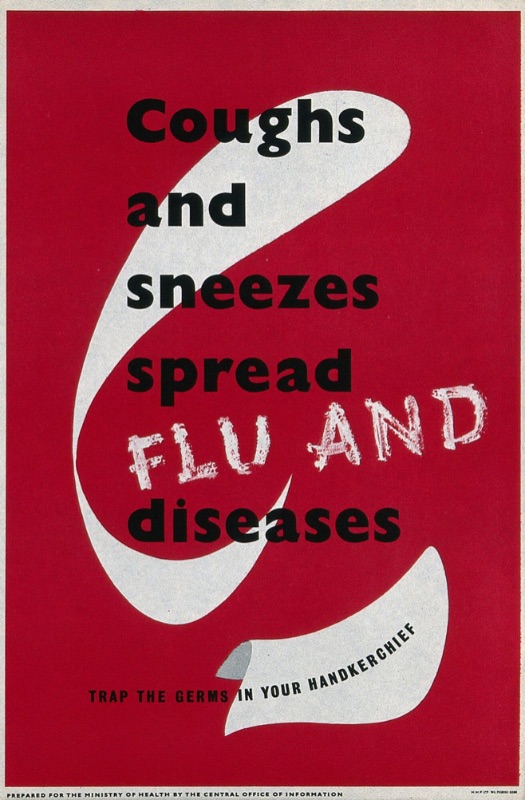

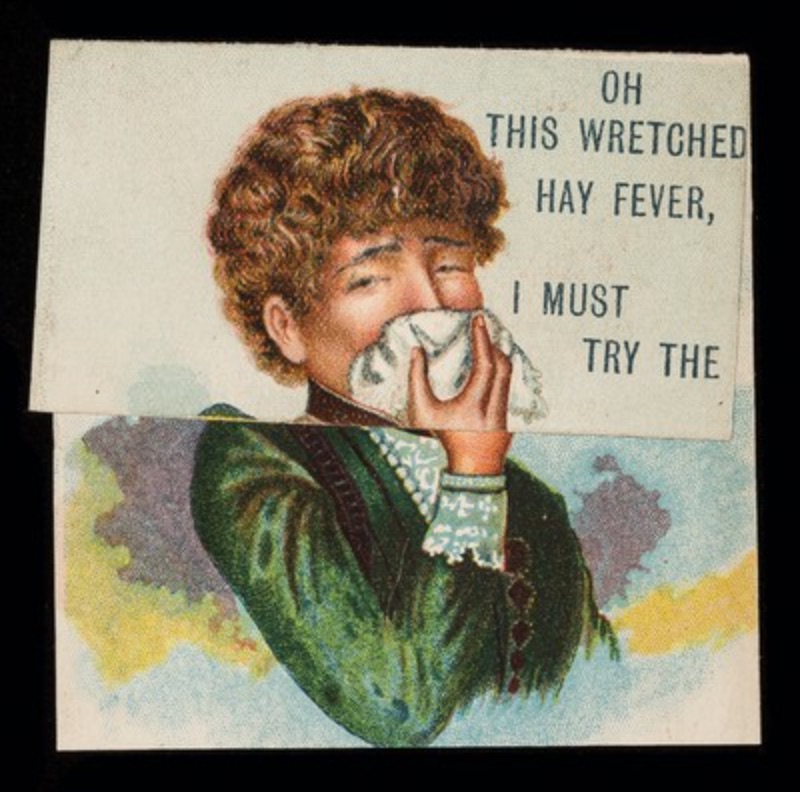

“Do you have a handkerchief?”

Influenza, you little demon

Wash your hands!

How to be patriotic

Masquerade

Docs with guns!

Fast, Safe, Painless!

Magic Therapy

This project deals with earlier influenza plagues (such as the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic, known to most as the „Spanish flu“) but also with subsequent measures in dealing with the virus. As an information and graphic designer, I focus particularly on the illustrations, photographs and fonts that were used on posters, matchboxes or leaflets at the time, informing the population. Also in the context of today’s Covid 19 pandemic, filtering old influenza visualisations becomes interesting - isolating, wearing a mask, washing hands - many measures are reminiscent of today’s handling during the pandemic. As a Russian designer living in Berlin, I am paying close attention to the situation, from a Russian and German perspective. „Corona deniers“, as many people call them in Germany, often used the narrative of the influenza pandemic to play down the current situation. Racial blaming - where the virus came from or who caused it - could also be observed during the influenza epidemics and is being repeated today.

The well-known „Spanish flu“ was followed by the „Asian flu“ in 1957, „Hong Kong flu“ in 1968, „Russian flu“ in 1977/1978 .

The term „Spanish disease“ originates from a report by the Reuters news agency on the illness of the King of Spain on 27 May 1918. (The Spanish themselves rejected this naming, judging it to be anti-Spanish propaganda).

As was the case in 2019, when Donald Trump repeatedly referred to „Covid-19“ in a racist manner as the „Chinese virus“ or „Kung Flu“ in order to portray China as the culprit in the pandemic. Medially, this sparked outrage among many around the world - but his statements also resulted in anti-Asian racism spreading significantly during the Corona period.

Other names for the influenza virus were interesting. In Europe, the foreign virus was first called „Blitzkatarrh“, „Flandern-fever“, among British and Americans „three-day“, „knock-me-down“ fever or „purple death“, in France „la grippe“ or „bronchite purulente“ (purulent bronchitis), among French military doctors so-called „maladie onze“ („disease 11“). In Spain, it was initially called „Soldado de Nápoles“ (Soldier of Naples), named after a song (performed in the musical theatre Zarzuela) that was very popular at that time. In Japan it was called „sumo kaze“ (sumo cold).

The meaning of the German term „Grippe“ also allows different theories. On the one hand, it is borrowed from the French „grippe“, meaning „fashion“ or „fancy“; phonetically, the word is reminiscent of the Czech word chřipka, or Russian хрип (chrip) or Polish chrypka, meaning „hoarseness“.

„Influenza“, „The Flu“ or „die Grippe“ and whatever you want to call it, is far from being defeated. Since the influenza virus is constantly changing (mutating), it is necessary to keep updating the vaccine.

Today, people are largely „immune“ to the influenza virus. It is practically one of the most common illnesses each year, especially during the winter season - or so-called „flu season“, „Grippewelle“ or „пик гриппа“. Flu is not as deadly as used to be. However, the constant adjustment of vaccination protects us just as much against the emergence of a new pandemic.

The general intensive study of the influenza by scientists can also be justified by the fact that the „Spanish influenza“ was counted as the worst of all pandemics back then. Especially since it occurred in 1918 in the midst of the First World War. Conversely, the war overshadowed the pandemic, making it much less of a sensation among the general population.

Today’s society considers influenza to be commonplace and rather unimportant. This makes it all the more exciting to take a look back at the history and the present day - especially in the light of Covid-19.

Alisa Verzhbitskaya

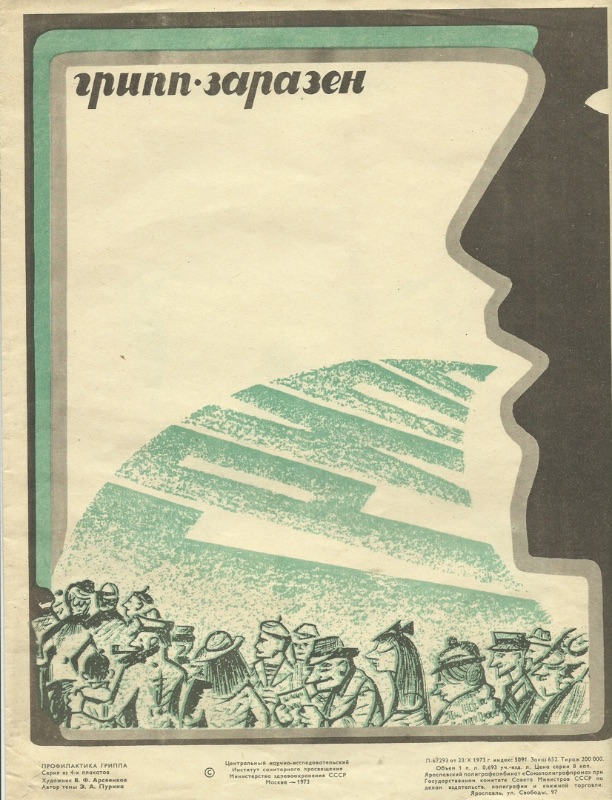

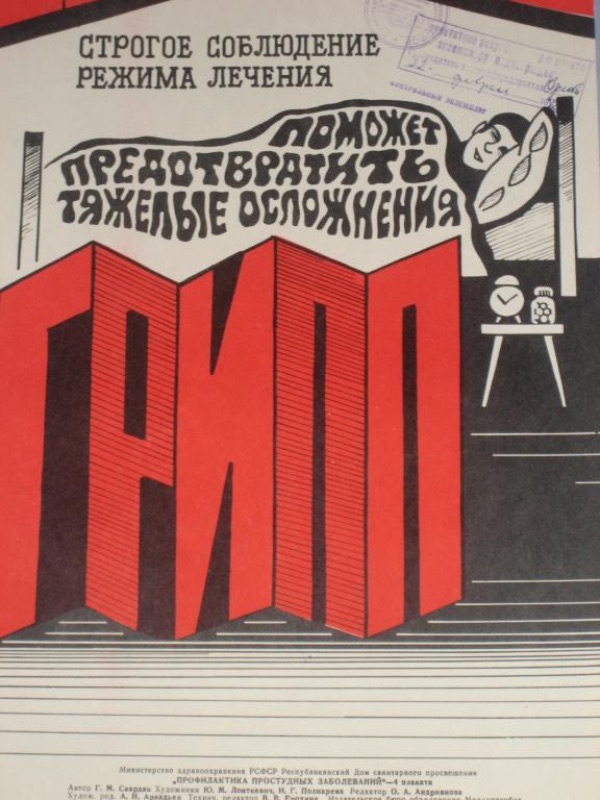

Pronounced as the word "Gripp", it is the name for the influenza virus. On the poster, the invisible danger is illustrated typographically. A closer look reveals small dots that make up the letters. Onomatopoeically, the word "gripp" is reminiscent of the Russian word "chrip", which means "hoarseness". The metaphor makes the representation all the more powerful. The breath, silhouetted from the mouth, describes how the virus spreads. The text above says "flu is contagious".

This exciting visualisation could also be found on other posters. Below, the concept was implemented in different ways.

Poster Artwort by A. V. Federovich © The Russian Museum of Military Medicine

UdSSR Poster 1969 by Verlotsky, Yefim Abramovich © Public domain sovietvisuals.com

UdSSR Poster. © Unknown Artist

1973 © E. A. Verlotsky

Paper handkerchiefs are a relatively recent phenomenon, historically speaking. Especially from a European perspective. For example, in ancient Japan and China, people were already blowing their noses with paper tissues and then burning them. In Europe, handkerchiefs made of cloth are much older and the history behind them conceals many facets.

Using handkerchiefs to wipe our noses seems self-evident to us today. Yet the cloth was used in other ways, also culturally different:

Historically, the variety and uses of small handkerchiefs that people carried in their pockets, in their hands or on their clothes were quite large: they were used to wipe the mouth or sweat, they served decorative or liturgical purposes and they were used for non-verbal communication. If used at all for blowing the nose, then this was only one function among many. - Susanne Preuss , contribution to the Wien Museum on the history of the handkerchief

For a long time, handkerchiefs were regarded as utensils of the upper social class. The people blew their nose into or through their fingers and then wiped them on their clothes, for example. The handkerchiefs were often designed with decorative patterns; ordinary people could not afford this luxury. Only with the advance of industrialisation and the establishment of the paper handkerchief this object became an affordable mass product.

"The handkerchief is the most dangerous of all items in daily use." – described Dr Hope Bridges Adams Lehmann, a British woman in Germany in 1880.

In the late 19th century, when bacteriology was rising rapidly in science, the attention before invisible pathogens became great. Interestingly, the handkerchief was identified as a particular source of danger. Unlike today, many handkerchiefs were used several times after use and were also sometimes handed on to others (for example, many mothers used a handkerchief to wipe their own and then their child's hands and nose). In addition, no one had a washing machine that could have been used to clean the handkerchiefs.

At that time, one had to hope for a more hygienic alternative or appeal to the citizens. The main rule was: 1. use the handkerchief for one day at the most and 2. keep the handkerchief for personal use and not to lend it to others.

In many images researched, the (flying) handkerchief was found as a recurring symbol. The depictions have the effect of instructions on how to use the handkerchief: they illustrate how to protect yourself and others from the pathogen. In many motifs, the handkerchiefs are ornamented and look like cloth handkerchiefs. This leaves open whether it was appealing to the whole population or a segment of the population.

A handkerchief being blown away by a sneeze. Colour lithograph, 1946. © Wellcome Collection. In copyright

The use of handkerchiefs to prevent flu and other diseases. Colour lithograph, ca. 1950 (?). Great Britain. Central Office of Information. © Wellcome Collection

UOh this wretched hay fever, I must try the ... Carbolic Smoke Ball : gives instant relief. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company. Date [between 1890 and 1899?] © Wellcome Collection

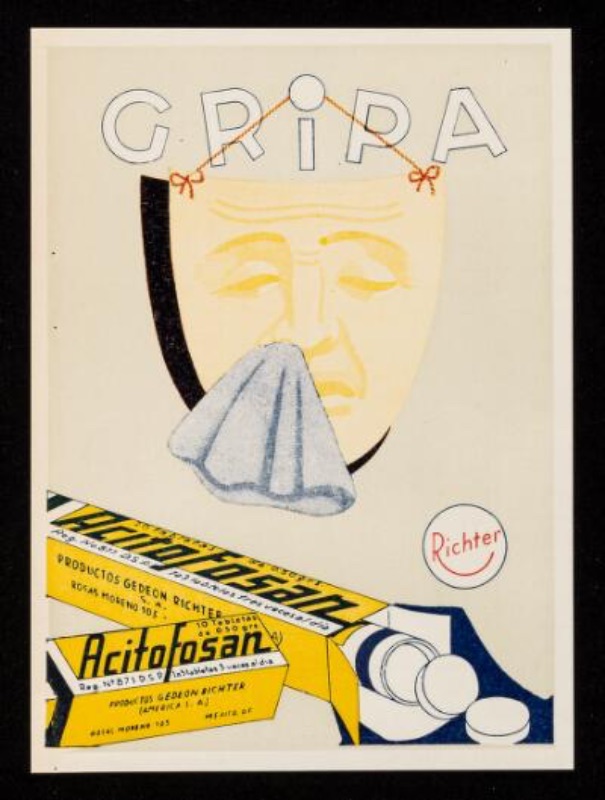

Gripa : Acitofosan / Gedeon Richter (América), S.A. Gedeon Richter (América) Date [1947] © Wellcome Collection

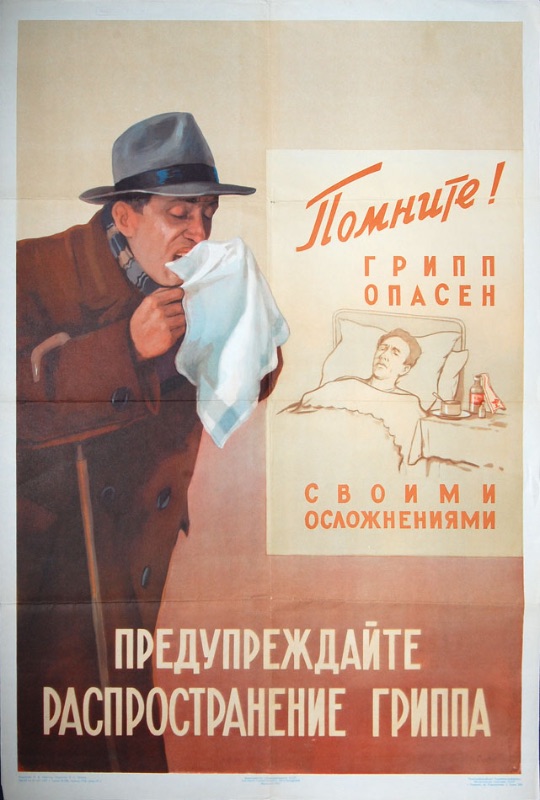

© Public Domain Kino-ussr.ru

After some time, the Japanese government realised the danger the virus posed.

Other than today, the population was medically and scientifically poorly prepared for the disease.

In order to protect the Japanese population from the virus, the government published a book containing the knowledge about the influenza virus to date - with a total of 455 pages.

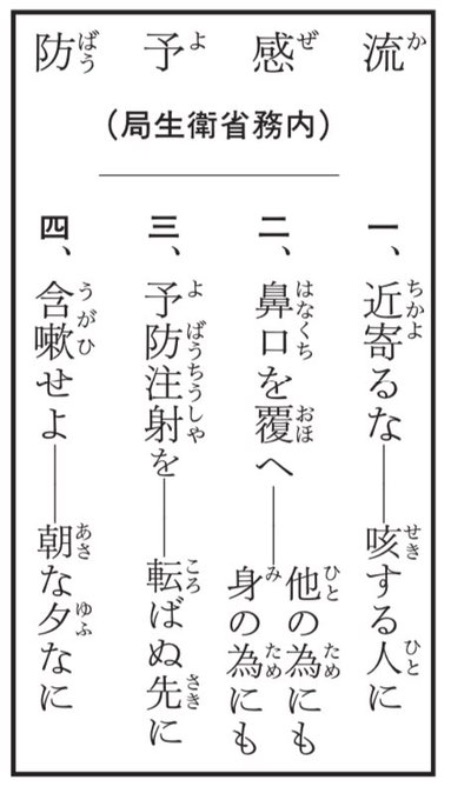

A guide listed the four rules, which can be translated as:

No.1: Stay Away (Social Distancing),

No.2: Cover your mouth and nose,

No.3: Get Vaccinated and

No.4: Gargle.

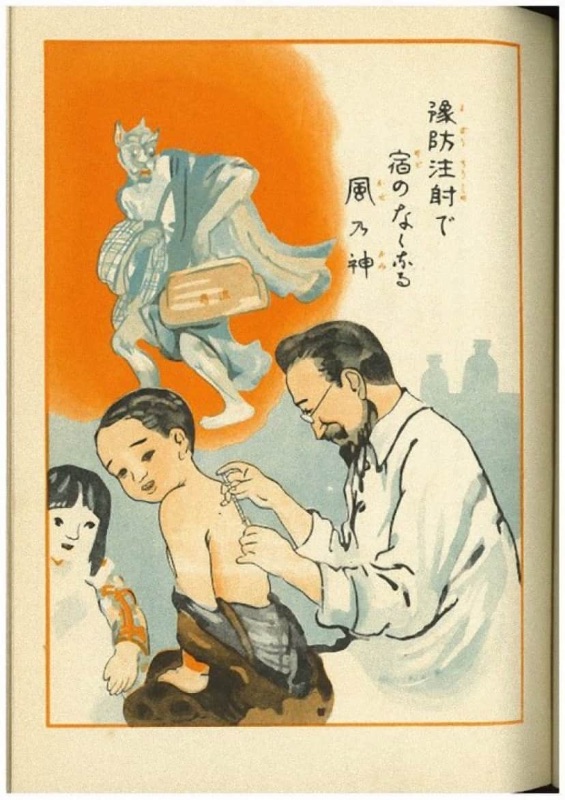

The book also contained several illustrations. The examples explained how to deal with the virus at home and in public places.

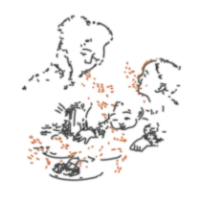

In the illustrated poster, a mother sitting at the dining table with her children is depicted as a danger to her children. What I find most interesting are the red and white strands flying out of her mouth. The artist often made use of this visualisation in his paintings. This simple depiction made the spread of the virus very clear. Unfortunately, I could not find out the artist's name. However, "Cover your mouth!" is written on the illustration. A small monster sits on her shoulder and maybe personifies the disease. I searched for the name of the monster for a long time, or in each case for a demon that reminded me of a mixture of a lizard and a human being.

Through my interest in manga and anime, I remembered the term "youkai". Demons from Japanese folklore - some are malevolent, others devious. Youkai are characterised by animal and human traits. Whether it depicts a youkai sitting on her shoulder, I could not find out. However, something else fascinated me: the mythical creature "Amabie", which is described as a mermaid or merman and is a creature that rises from the sea and predicts an epidemic.

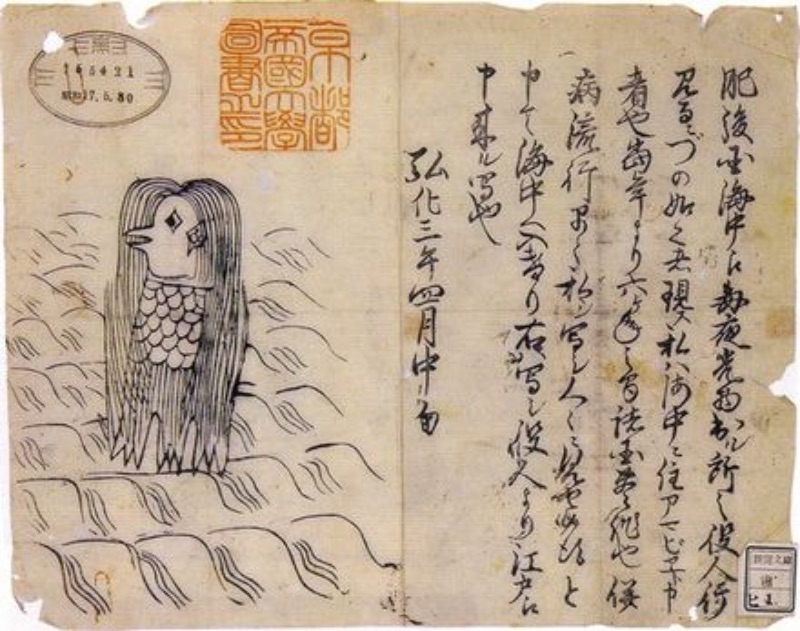

Not only this woodblock print from the later Edo period (1 January 1846) shows Amabie - the mythical creature was also re-discovered during the Corona pandemic in Japan and was used as a mascot.

That was my little excursion into Japanese mythology.

The 4 rules of preventing the flu. A Japanese Guide To Beating Killer Flu from 1918 © Library of National Institute of Health Sciences Japan; karapaia.com/archives/52290283.html

This poster warns that if you cough without covering your mouth, germs will spread. A Japanese Guide To Beating Killer Flu from 1918 © Library of National Institute of Health Sciences Japan; karapaia.com/archives/52290283.html

A Japanese Guide To Beating Killer Flu from 1918 © Library of National Institute of Health Sciences Japan; karapaia.com/archives/52290283.html

Amabie (the mermaid that foretold a plague) from kawaraban (newspapers of the Edo era) © Wikimedia Commons

STOP! Kansen Kakudai COVID-19 (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) © Wikimedia Commons

"Since the Enlightenment, the concept of hygiene has been a key element of modern society and has left a lasting mark on our perception of everyday reality. Hygiene functioned as the cradle of the modern subject in modern times [...]. In the Bolshevik experiment of the 1920s-30s, one of the core elements of the socialist project was the creation of a "Soviet body" – optimised according to aesthetic and medical-hygienic norms. The concepts of hygiene, cleanliness and health did not only include personal hygiene, but also the construction of the Soviet identity.

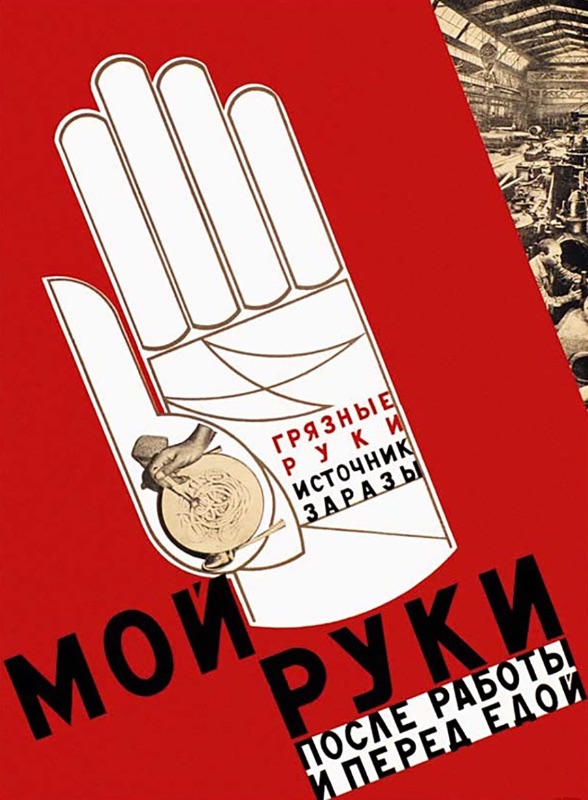

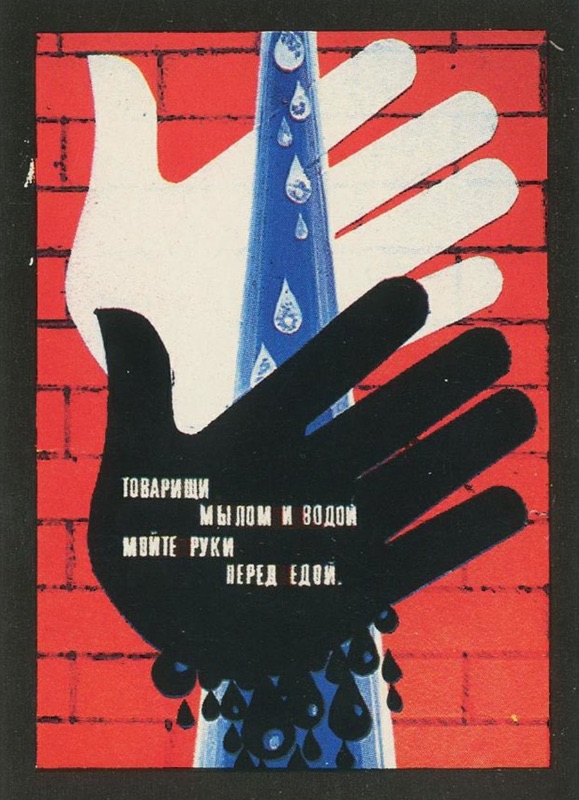

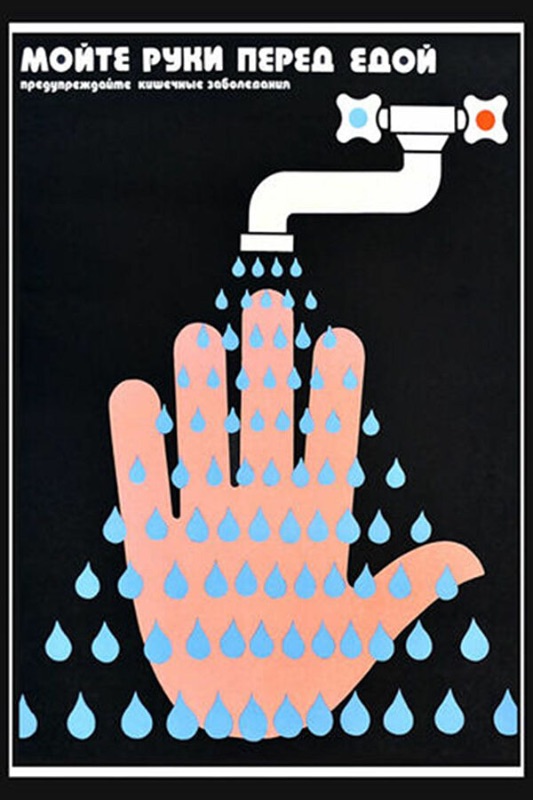

During my research, I discovered various illustrated examples of the concepts of cleanliness, hygiene and health: perfect and trained bodies, preventive measures such as opening windows, isolating oneself when sick, remarks such as " When you finish work, go to the sauna!" or washing your hands before and after every activity. This is only a small enumeration of Soviet "hygiene propaganda".

Here follows a selection of different illustrations on the subject of "Wash your hands!

Wash your hands after work and before eating. Dirty Hands are a source of infection 1931 © Public domain sovietvisuals.com

Wash your hands © Public domain Schubina G. K.; sputnik-odessa.ru

© Archive photo rbth.com / Russia Beyond

© Archive photo rbth.com / Russia Beyond

Wash your hands before your eat.Illustration on match. © match-museum.ru

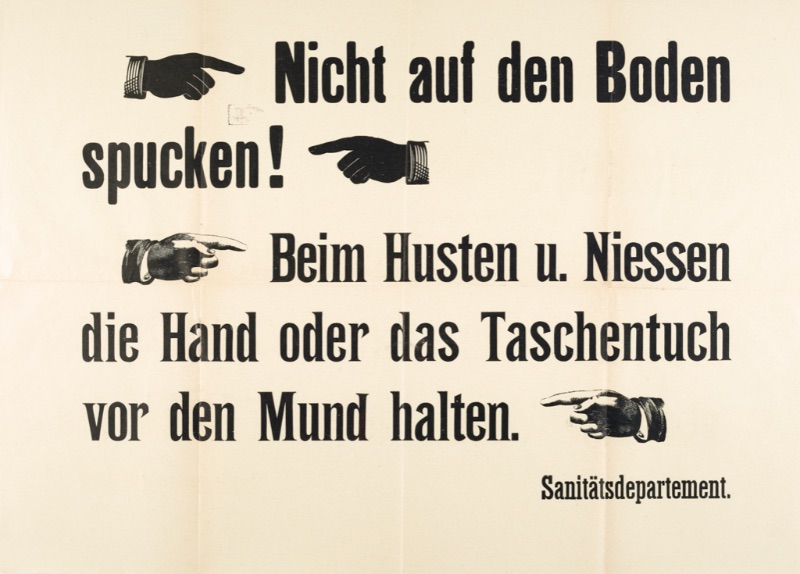

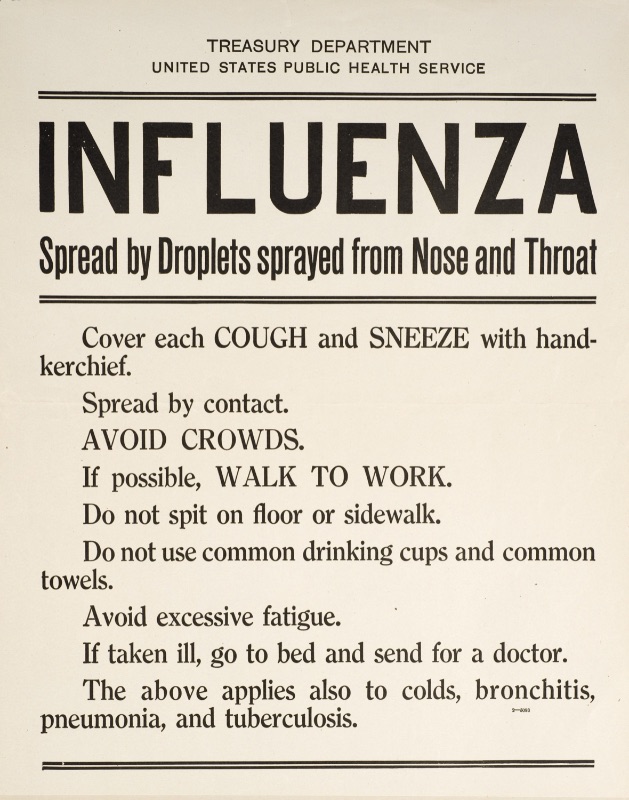

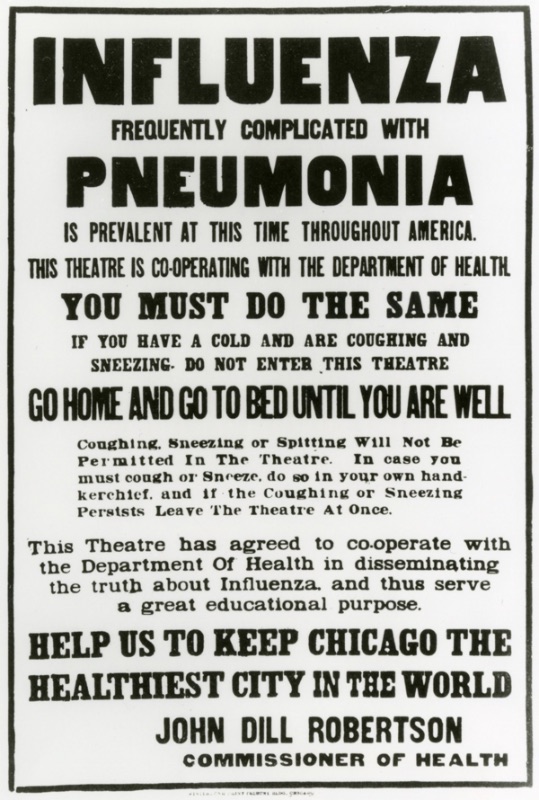

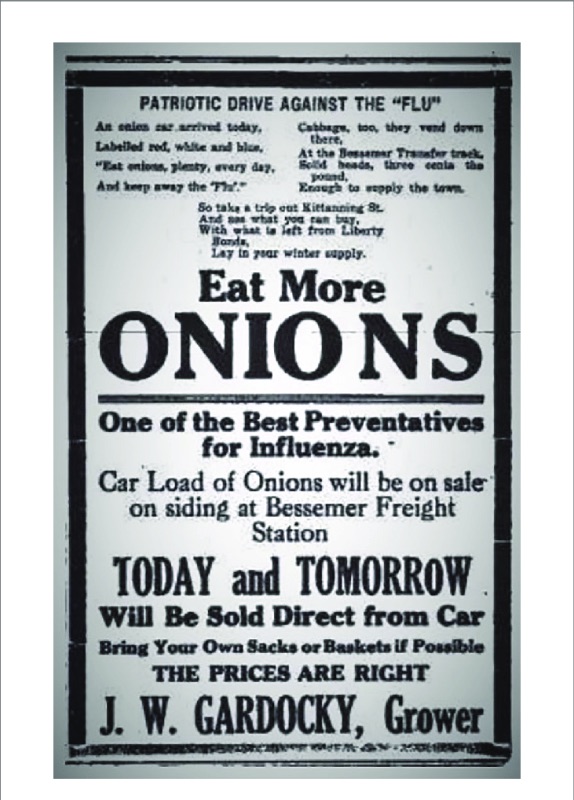

"Don’t spit!“, „go home until you are well“, „avoid crowds“, „eat more onions“ and „help us to keep Chicago the healthiest city in the world."

Ban on spitting in German during the „Spanish Flu“ (StABS Sanität 3.3.) 1917 - 1921.© Online archive catalogue of the State Archives Basel-Stadt; https://query.staatsarchiv.bs.ch/query/detail.aspx?ID=315900

Influenza spread by droplets sprayed from nose and throat. Public health poster with instructions for preventing the spread of influenza. Distributed during the influenza pandemic of 1918. © Public Domain Images from the History of Medicine (IHM)

Influenza frequently complicated with pneumonia is prevalent at this time throughout America. Photograph of poster relating to the epidemic of influenza in Chicago occurring during the fall of 1918. © Public Domain Images from the History of Medicine (IHM)

Propaganda poster that got popular during the 1918 flu pandemic in the USA. From reddit.com © Image under the CC-BY-NC-SA lnternational Creative Commons License.

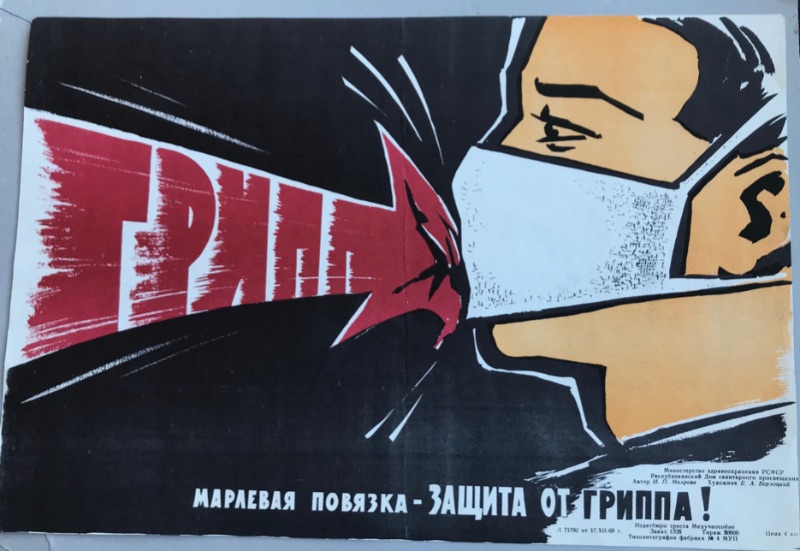

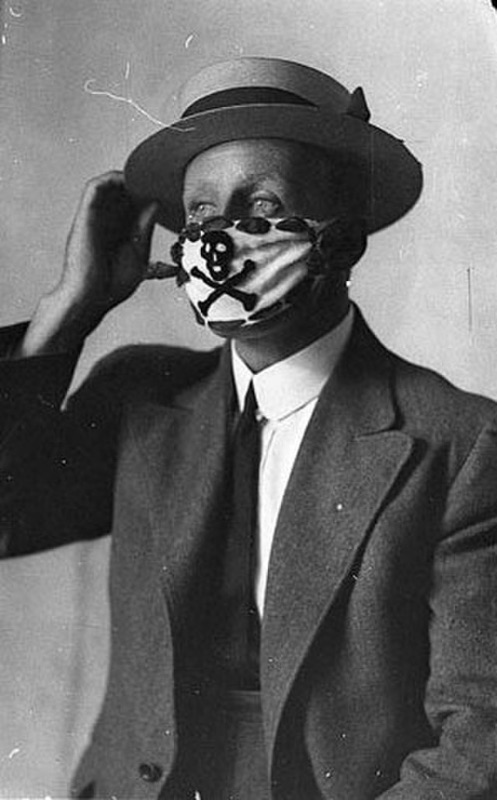

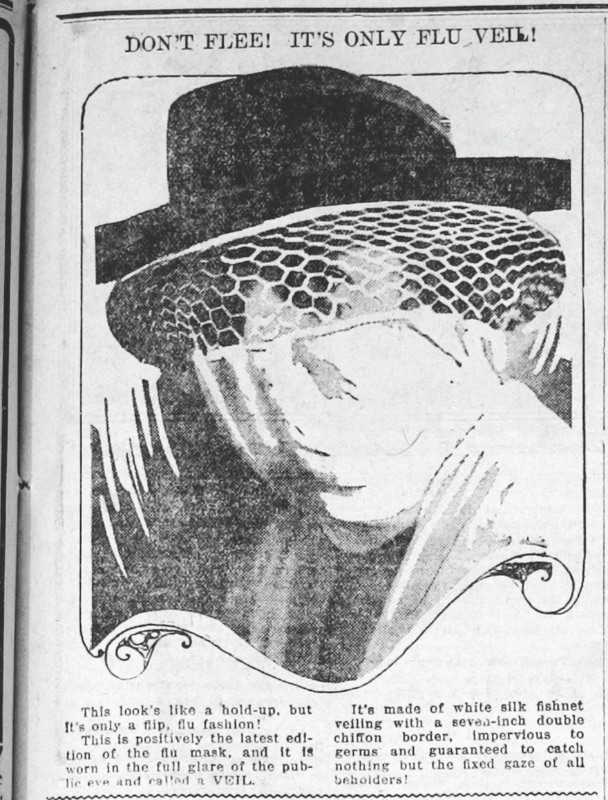

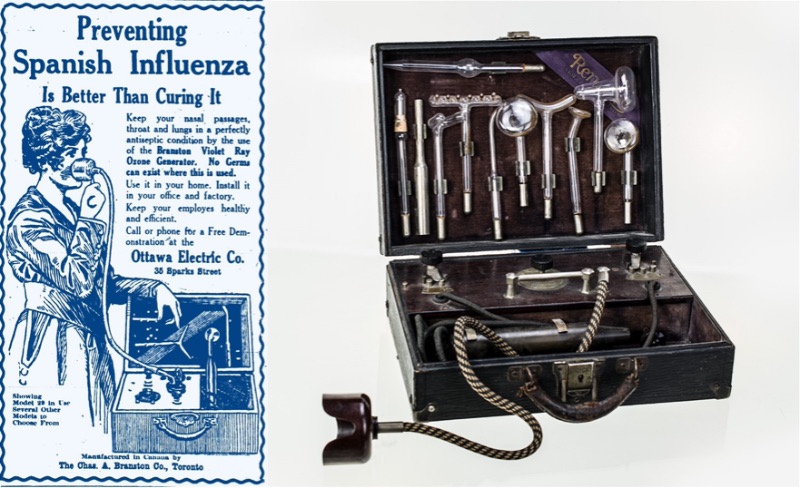

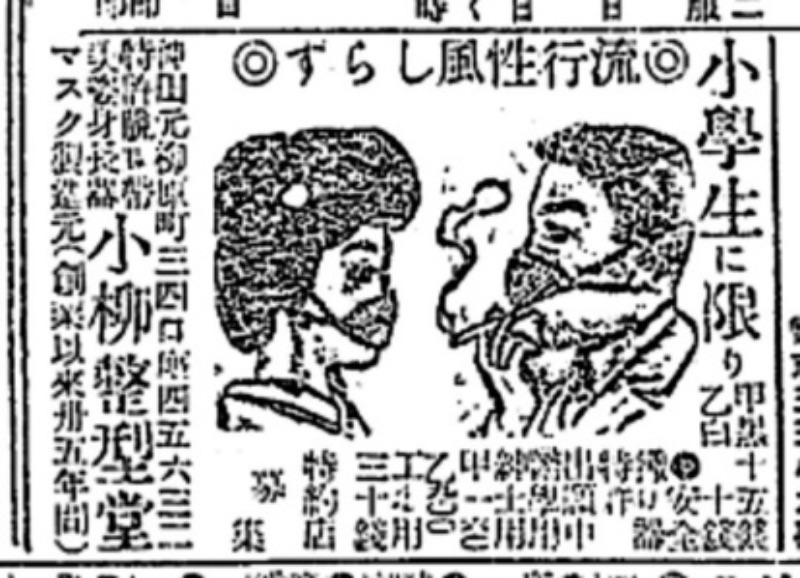

Covering your mouth and nose may not only protect you from germs. It can also be a fashion statement, something innovative or urban, but also a political force.

Compulsory mask, brought in to combat the flu epidemic after the World War, 1918-1919 / Sam Hood Note: The skull and crossbones on the mask was a joke, not part of the mask as issued, in an attempt to halt the disease. 12,000 died in Australia and between 20-100 million around the world, more than were killed in the War © Hood, Sam, 1872-1953. STATE LIBRARY NEW SOUTH WALES

Don't Flee! It's Only Flu Veil! 1918-11-14. Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, © University of Utah

Branston Generator (right), c. 1918. Art and Heritage Centre of the MUHC, 2012-0204; with a clipping from the Ottawa Journal, October 19, 1918 © Art and Heritage Centre of the MUHC

An advertisement for a mask published in the Asahi Shimbun (23 January 1920) during the Spanish flu epidemic. Originally, masks were used in mines and factories, and at that time many of them were dark and small. © Asahi Shimbun 1920

L'Oeuvre, 6 March 1929. Gallica © Bibliothèque nationale de France

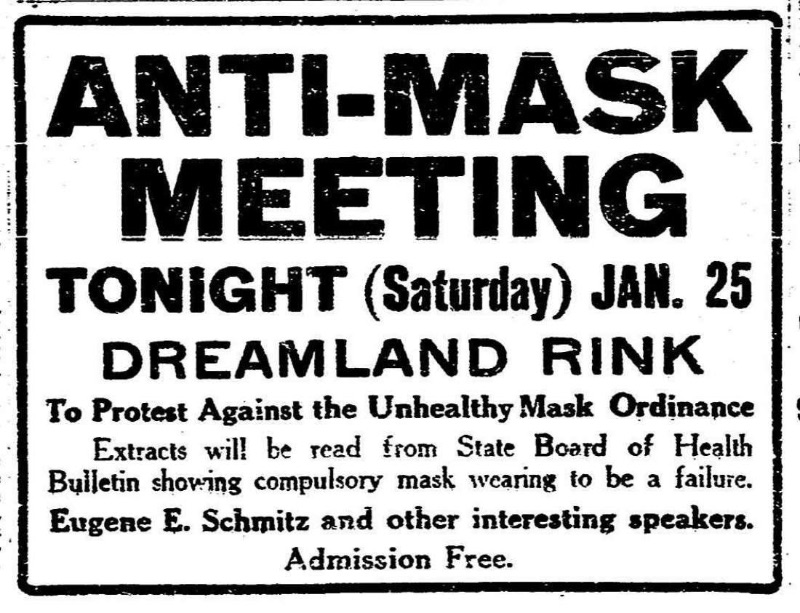

An advertisement for the Anti-Mask League, protesting a city mask order, ran in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1919. © The Chronicle 1919

Vaccination guns were used for mass vaccination and were an alternative to the needle. They were used for different vaccinations, influenza was among them.

The vaccination guns are no longer used and are considered risky because, among other things, they could transfer blood or biological material to other patients. The WHO stopped recommending them a long time ago.

From today's perspective, the pistols look terrifying. The many old photographs give me the impression that they were trying to convince people to vaccinate.

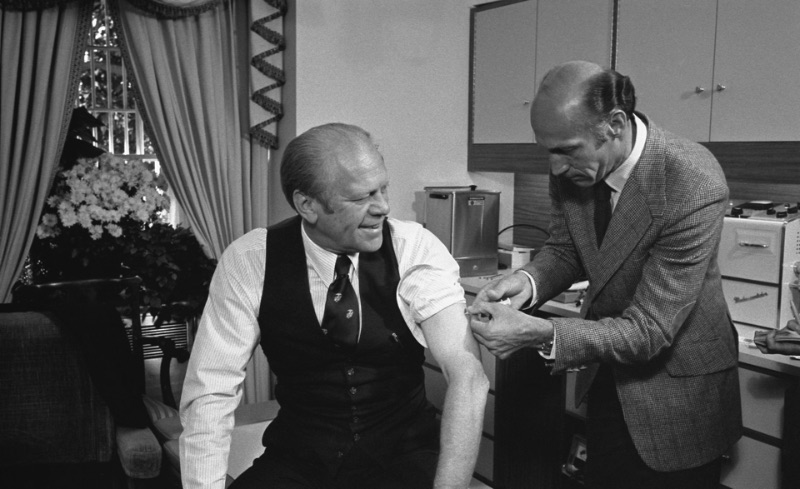

Many photographs show not only ordinary citizens, but also models, presidents, nuns being vaccinated by a trusted doctor (usually male) and posing proudly. Whether with a gun or a needle, in line with the idea: "if even U.S. President Gerald Ford can get vaccinated, so can I."

Multidose Jet Injection Apparatus, known as "PED-O-JET", hydraulically powered, with carrying case, by ScientificScience Museum Group Collection© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

An adult female receiving a vaccination that was administered by a public health clinician, by way of a jet injector during the nationwide swine flu vaccination campaign, which began October 1, 1976. © Wikimedia Commons

Vaccination against Hong Kong flu by State Health Department in 1969. © Karlsruhe City Archive

This photograph depicts President Gerald Ford receiving a swine flu inoculation from his White House physician, Dr. William Lukash on October 14, 1976. © Courtesy Gerald R. Ford Library

German politician Markus Söder receives a flu vaccination from former Bavarian Health Minister Huml on 8 November 2016. © Michael Lucan Wikimedia Commons

Convincing people to get the flu vaccine didn't sound so easy back then. Even I would first be simply sceptical or uninterested and ask myself: why do I need this? Is it safe? But how was the public confronted with it at the time? In my research, it was difficult to find vaccination posters on influenza alone - especially with little prior knowledge.

Influenza vaccination has probably only officially existed since about 1942 (according to wikipedia). Interestingly, the effectiveness of influenza vaccines is much lower than that of other vaccines - there is still no safe medical protection against influenza. For this reason, vaccines have to be adapted to the new mutation year after year (as the World Health Organization reports in this regard).

Old posters I found on influenza vaccination addressed different target groups. It was advertised as particularly important among children and older generations, people with a previous illness, but also people of all classes and cultures - in effect, to everyone.

And in the past, the virus seemed to be unknown and dangerous - nowadays, the annual vaccination (especially in winter) is more normal than ever.

Here are a few little notes I made on the posters:

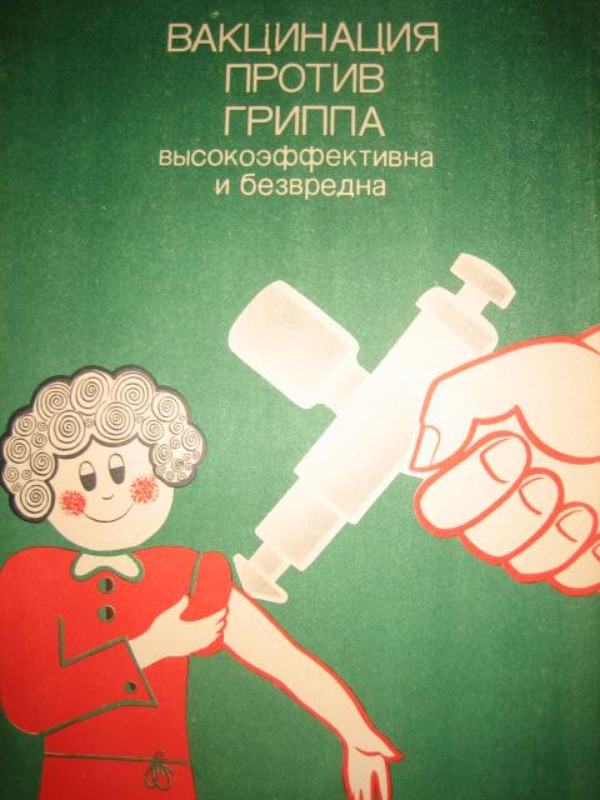

1) Unclear if this is an old granny, or a small child. The person, presumably a woman, looks quite happy, even though the vaccination gun is so immensely large. To me, this gun definitely looks quite threatening (I'm not even a fan of syringes).

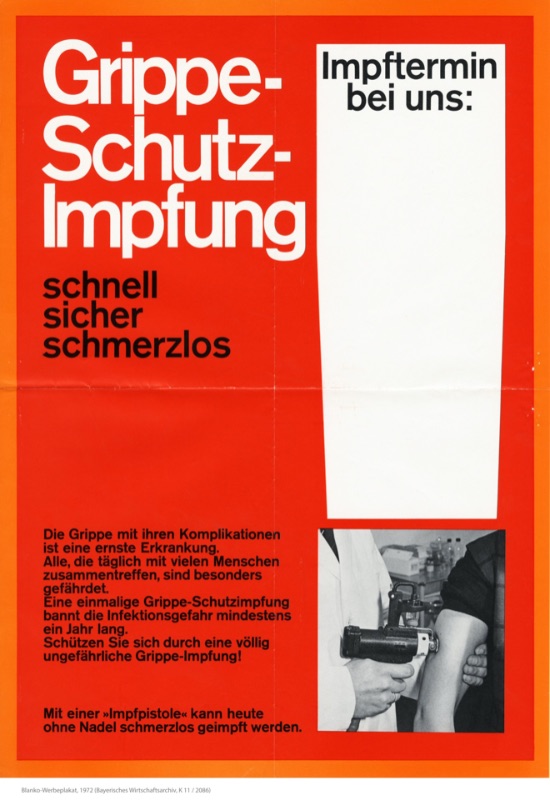

2) “With a "vaccination gun" it is possible today to vaccinate painlessly without a needle." - says the bright red poster with a huge exclamation mark. Fortunately, this vaccination gun no longer exists.

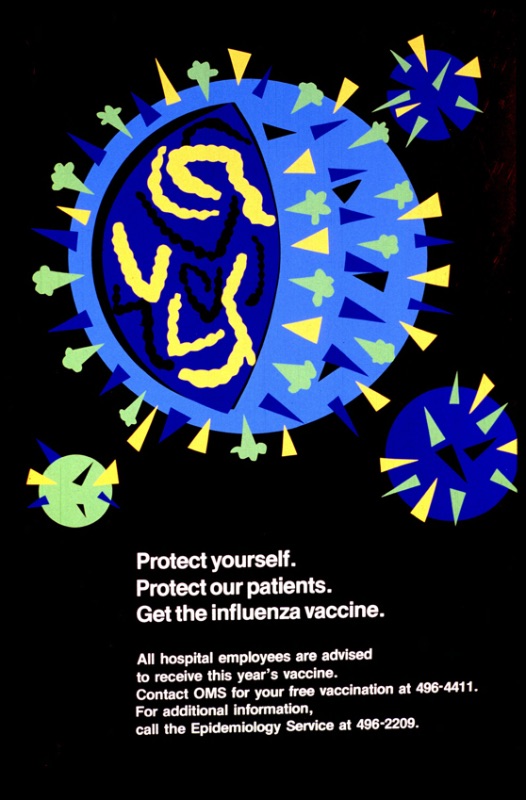

3) The visualisation of the virus is strongly reminiscent of the images we also saw in the beginning of Corona's pandemic. Pretty cute how they worked with simplified geometric shapes like circles and triangles. Even a little extra to see it without being a 3-D graphic.

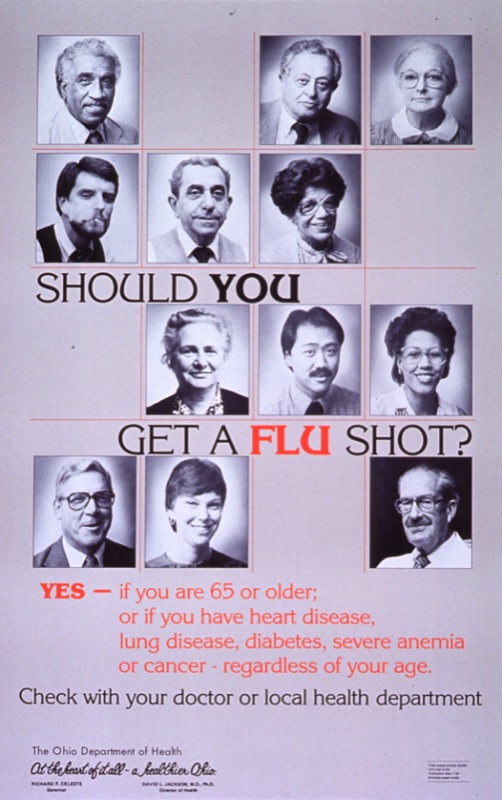

4) I found the poster quite strange. On the one hand, the description of the National Library says something about "consists of (...) photo reproductions showing people of all ages and races", and the arrangement of the portraits is in the shape of a swastika - hidden message or did the designers not think of anything?

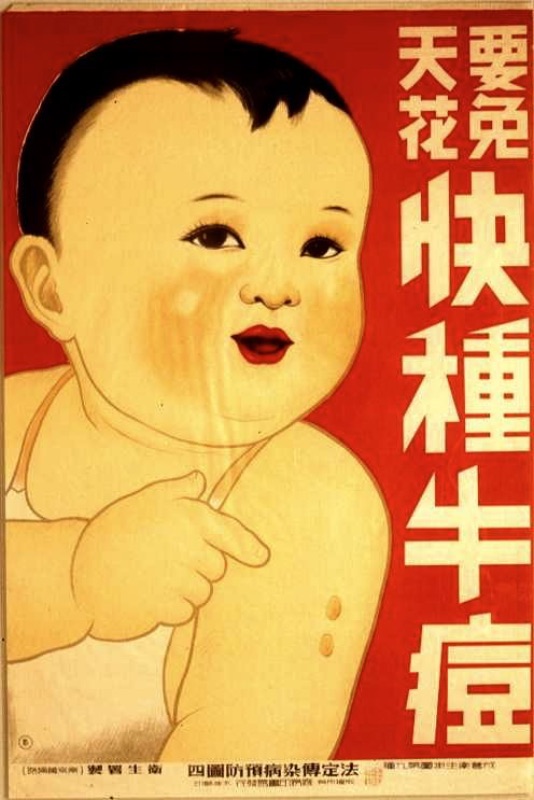

5) The little baby is presented in a very adult, "rational" way. Self-confidently it points to the upper arm and motivates to vaccinate. When I was a little child I was terrified of any needle. I think many small children feel that way.

"Flu vaccine is highly effective and harmless" Soviet health poster, 1983 © Public Domain Soviet Visuals

„Schnell, sicher, schmerzlos“ – „Fast, safe, painless“ - flu shot poster from 1972 © Bayerisches Wirtschaftsarchiv BWA

A round virus is shown, with pointed objects on the outside wall and chain-like objects on the inside. Three similar but smaller circles surround the larger one. (198-?) © Public Domain National Library of Medicine

Should you get a flu shot? Taupe poster with black and red lettering. Title at center of poster. „Visual image consists of b&w photo reproductions showing people of all ages and races.“ Caption appears below photos. Publisher information and motto--At the heart of it all-a healthier Ohio--at the bottom of poster. © National Library of Medicine

Chinese Poster. „You have to be fast with vaccination shot if you want to prevent your child against diseases.“ (Date unknown) © Unknown

When influenza hits you, there are a few ways to get better quickly.

Family, friends and doctors tell you the same thing over and over again: drink tea, sleep, rest.

But have you heard about the latest effective cure for the flu? No? Neither have I. A look into the past may provide new inspiration.

Leaflet advertising Garnett-Pickles Co. Limited's vaporizer for respiratory diseases. The illustration shows a woman using it. London : Garnett-Pickles Co. Limited, [between 1900 and 1915?] © Wellcome Collection. Public Domain.

Advertising insert for Laboratoires Le Brun's Eucalyptine (distributed in Cuba by Brunschwig & Co.) for influenza, cough, bronchitis, asthma and whooping cough. [1942] © Wellcome Collection. In copyright

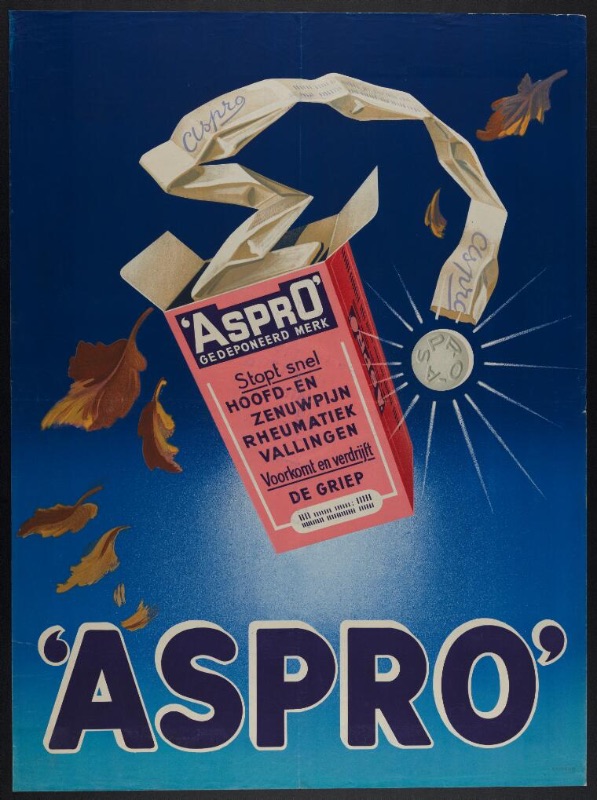

A box of Aspro (analgesic and flu remedy) among falling autumn leaves. Colour lithograph after Damour, ca. 1930 (?). [The Netherlands] : [publisher not identified] © Wellcome Collection. In copyright

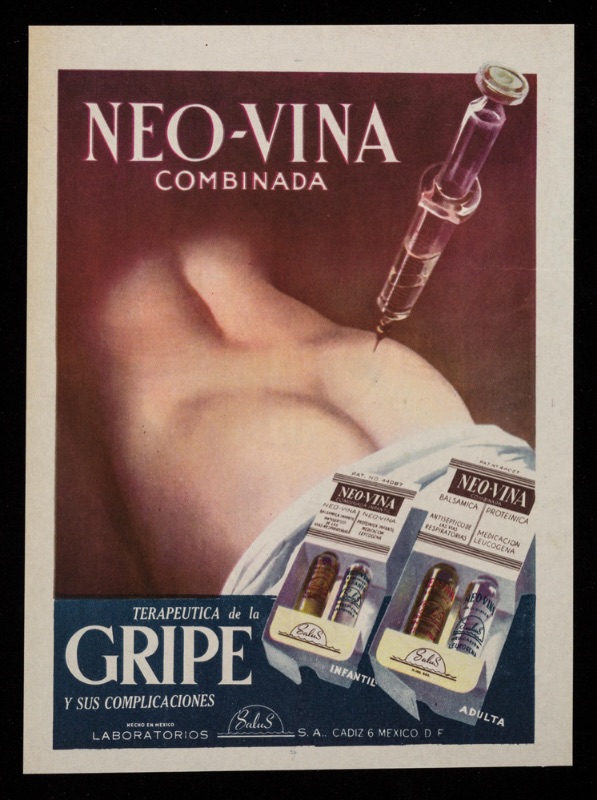

Neo-Vina combinada : teraputica de la gripe y sus complicaciones / Laboratorios Salus S. de R.L Advertising insert for Laboratorios Salus's injectable Neo-Vina for influenza and its complications (showing a large syringe plunging into a pair of buttocks) and a range of variations for diseases of the respiratory tracts. [1949?] © Wellcome Collection. In copyright

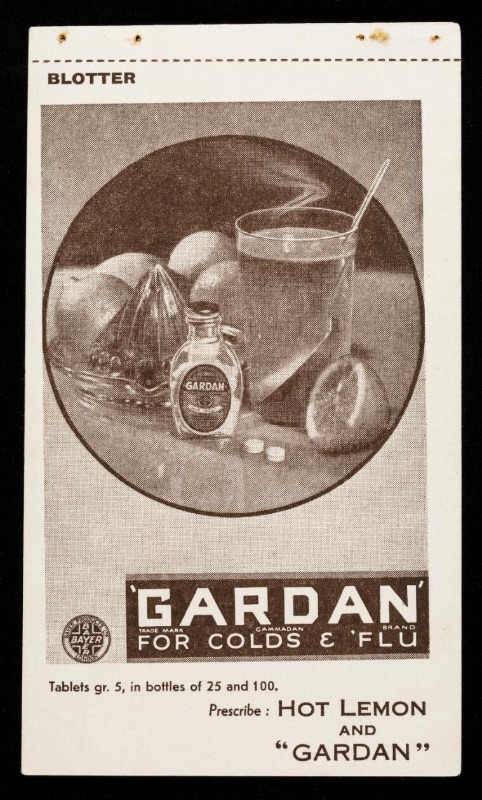

'Gardan' for colds & flu. One of a series of blotters issued by Bayer Products Ltd. advertising Gardan, active against colds and flu, showing a photographic image of hot lemon and "Gardan" in a glass. London : Bayer Products Ltd., [between 1930 and 1939?]© Wellcome Collection. In copyright